Sign Indicating the entrance of Zapatista rebel territory. “You are in Zapatista territory in rebellion. Here the people command and the government obeys”. (Photo by Massa P., 2003, CC-BY-NC.)

Sign Indicating the entrance of Zapatista rebel territory. “You are in Zapatista territory in rebellion. Here the people command and the government obeys”. (Photo by Massa P., 2003, CC-BY-NC.)

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) laud free trade as a doctrine of economic growth, prosperity, and development. Free trade agreements (FTAs), agreements between two or more countries to reduce mutual barriers to trade, thus easing the flow of investments, capital, and labor across borders, have proliferated rapidly since the 1980s. However, a critical question we must ask, particularly when examining agreements between countries with political and economic power asymmetries, is who benefits from free trade agreements? By examining the case of NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement, now known as the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement), we can see that Indigenous peoples are often disproportionately harmed by the doctrine of free trade, which works more to expand the reach and power of multinational capital and continue legacies of colonial dispossession than it does to bring prosperity to people’s lives. For Mexico’s diverse Indigenous communities, NAFTA has been especially destructive to the practice of food sovereignty.

Indigenous food sovereignty describes the right of Indigenous peoples to self-determined, healthy, and culturally appropriate food systems, including being able to practice traditional foodways on ancestral lands. By slashing the viability of traditional corn-growing livelihoods, forcing migration, threatening seed saving, and eroding communal land rights, NAFTA has been one of the biggest threats to Indigenous survival in contemporary Mexico. However, Indigenous peoples have effectively fought the harms of free trade and cultivated food sovereignty through movements like the Zapatistas.

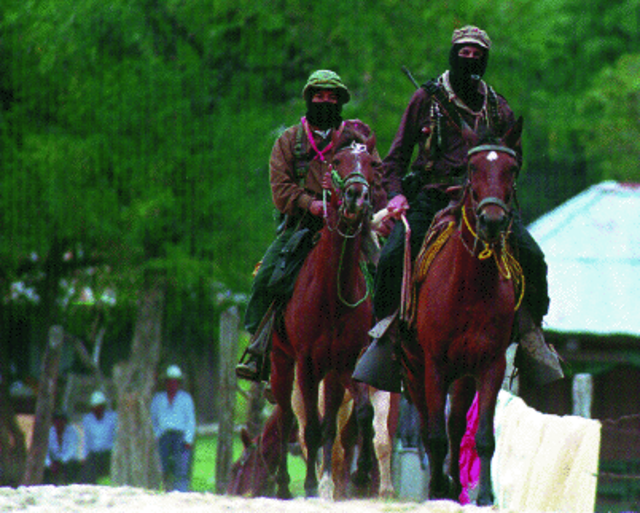

Foreseeing the damage that NAFTA would inflict on rural economies and, in turn, Indigenous peoples, campesinos, and other socio-economically marginalized groups in Mexico, the Zapatista movement rose against the Mexican government on January 1st, 1994, the same day NAFTA went into effect. The Zapatistas, composed largely of Mayan people (including Ch’ol, Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Tojolobal, Mam, and Zoque Maya peoples) (Gahman, 2017) and informed by Mayan worldviews, are based in southern Mexico’s Chiapas state. The Indigenous population in Chiapas is Mexico’s third largest, at 1.1 million (Godelmann, 2023). Despite being one of the country’s wealthiest states in natural resources, most of its Indigenous population (70%) suffers from malnutrition. It faces consistent poverty and exclusion from governmental decision-making processes (Godelmann, 2023). The Ejército Zapatista de la Liberación Nacional (EZLN), the Zapatista’s liberation army, was created to represent Indigenous demands in response to hundreds of years of oppression, exploitation, dispossession and segregation (Godelmann, 2023). To understand why the Zapatistas have called NAFTA a “death certificate” for Indigenous people (Gahman, 2017), we can turn to its impact on traditional agricultural livelihoods.

In Mexico, the agricultural sector, in particular small-holder land work, is dominated by Indigenous peoples (Minority Rights Group, 2024; Pérez Velasco Pavón, 2014), with approximately 67% of Indigenous peoples working in farming (Commission for Indigenous Development, 2002, cited in Godelmann, 2023), compared to approximately 13% of the general population (World Bank, 2022). Most Indigenous peoples in Mexico rely on farming activities to support profitable livelihoods for their households (Fierros-González and Mora-Rivera, 2022), and many rural Indigenous communities rely on farming activities as a primary food source. The main reason NAFTA has been a “death certificate” for Indigenous peoples is its impact on these agricultural livelihoods, cutting both incomes and access to food. Subsidized US corn flooded Mexican markets in response to reduced trade barriers (such as tariffs) between the United States and Mexico. This displaced the corn produced by Indigenous small-holder farmers and cut off their ability to make livelihoods from farming (Gahman, 2017). As a result of NAFTA’s devaluation of Indigenous-produced goods in local and national markets, Mexicans in already marginalized regions like Chiapas were thrust into deepening food insecurity (Gahman, 2017). Even as NAFTA has been re-adapted to the USMCA (United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement), food shortages and dependency on imported grains, mainly from industrial farming in the US, are only growing (Rocha, 2023). During NAFTA negotiations in the 1990s, 40% of Mexican farmers grew corn. The corn crops were hardest hit. Monthly wages for largely Indigenous self-employed farmers fell by around 88% from 1991 to 2003 (White, Gammage, and Paez, 2003). Furthermore, NAFTA resulted in 1.3 million Mexican farmers losing their jobs, impacting primarily subsistence and small-holder farmers (White, Gammage, and Paez, 2003). As a result, rural Indigenous communities were thrust into increased levels of poverty, leading to food insecurity and forcing people off of their land in search of work elsewhere. By causing people to emigrate from their homes for work, NAFTA contributed to disconnecting Indigenous Mexicans from their lands and traditional foods.

Farmers like Benacio Mendoza of Oaxaca faced the difficult decision to leave their communities due to their inability to continue surviving off of corn production in the face of the US imports given Mexican market access by NAFTA. He and many others had to migrate to cities, often as far from home as the United States. Mendoza ended up in Tennessee as a chef and was separated from his daughter for 18 years while working to support his family (Darlington and Gillespie, 2017). Like Mendoza, thousands of other Mexican farmers and rural community members migrated to work in Maquiladoras (Grassroots International, 2007; Ebner and Crossa, 2019). Maquiladoras are factories along the northern border set up by US companies to take advantage of cheap labor and lesser regulations. In Maquiladoras, primarily woman workers face wages that keep them in poverty (Figueroa, 2016), as well as manufactured health issues resulting from preventable labor rights violations, sexual harassment, exposure to toxic chemicals, and other pervasive human rights abuses (Nevarro, 2014). By exacerbating economic marginalization, which drives emigration from rural communities, NAFTA has contributed to the erosion of Mexican Indigenous food sovereignty by pushing Indigenous peoples away from land-based livelihoods on ancestral territories.

NAFTA has also weakened the seed ownership of Indigenous growers. The agreement has increased the power and market access of a few agribusiness corporations like Grupo Bimbo, Maseca, Monsanto, and Cargill, providing them immense profits (Rocha, 2023), while largely disempowering Indigenous communities. Seed regulations have been a central mechanism of this disempowerment. Provisions like the UPOV (Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants) enable these corporations to register and patent seed varieties (Bilaterals.org, 2023). With these patents, they gain monopoly control over the growth of certain strains of staple crops like corn. If Indigenous peoples continue to grow seeds that companies have patented, they risk fines and even imprisonment (Bilaterals.org, 2023). Using free trade agreements to their advantage, agribusiness companies thus reduce agrobiodiversity by supporting the mono-crop growing of patented seed varieties, as opposed to Indigenous farming methods, which can include more rotation, a higher diversity of seed varieties, and fewer chemical and industrial inputs. Seed patenting of crops grown in Mexico can even go as far as “biopiracy”.

Biopiracy describes the process whereby corporations illegally take Indigenous plant varieties and then patent them to gain exclusive commercial rights to their nutritious or medicinal uses without respecting ownership of or compensating Indigenous peoples for using their intellectual property (Imran et al., 2021). While companies often get away with biopiracy, recent efforts by Mayan people in Chiapas have successfully resisted the exploitation of their intellectual property over traditional plants (ICT, 2018).

Secure land rights are a critical precondition for food sovereignty and are under attack in Mexico due to NAFTA. For decades following the Mexican revolution, the ‘ejido’ system facilitated communal land ownership for subsistence and market cultivation by Indigenous peoples and campesinos, placing over 50% of Mexican land in their hands (Kilhart, 2016). In 1992, to accommodate NAFTA’s impending implementation, the Mexican government changed the constitutional provisions designed to protect Indigenous and peasant land holdings by abolishing the ejido system (Kilhart, 2016). Following the neoliberal logic of expanding the privatization of land holdings, this change attracted investment in land from prospectors. It resulted in the dispossession of Mayan lands in Chiapas by non-Native speculators (Forbes, 2010), who aimed to profit from these mineral, water, and gas-rich lands. This has hurt Indigenous food sovereignty by facilitating the transfer of land from its Indigenous stewards to foreign actors who seek to exploit its commercial value through mining, industrial agriculture, and water governance.

The Zapatistas represent one example of the many instances of Indigenous people actively resisting the negative impacts of free trade on food sovereignty. The Zapatistas resist dependence on multinational agribusiness by building local, autonomous, and agroecological food systems in their territories (Gahman, 2017). This includes land-based farming education for community members (Gahman, 2017), continuing the strong legacy of corn cultivation among Mayan people, and spreading food growing skills to increase food self-sufficiency. Zapatistas have also promoted food sovereignty and sustainability by creating committees to help Indigenous communities transition to agroecological farming methods (Hernandez, Perales, and Jaffee, 2020, cited in Salas, 2021). To combat the threat of genetically modified corn to the biodiversity of corn varieties in Mexico, the Zapatistas created the Mother Seeds in Resistance from the Land of Chiapas Project (Brandt, 2014). The project is designed to save “landrace” corn varieties: corn that farmers have selectively cultivated for generations to adapt to the specific climate and soil conditions of the region it is endemic. The project includes educating farmers about seed genetics, importing genetic test kits, and sending seeds to ‘solidarity growers’ worldwide (Brandt, 2014).

Through its threats to Indigenous-controlled farming, land rights, seed ownership, and community integrity, NAFTA continued many of the problematic legacies of colonialism in Mexico. Free trade agreements like NAFTA illustrate the dangers of placing the interests of large food companies above those of Indigenous and rural communities. As multinational corporations gain profits from market expansion and pro-foreign-capital policies, the economic shocks of neoliberalism are felt first and hardest by Indigenous communities. However, the Zapatista movement, along with other Indigenous movements across the Americas and the world, demonstrate that colonial legacies are not going uncontested. Through collective and direct action, Indigenous peoples effectively resist the harms of free trade agreements on their livelihoods and self-determination.

Brandt, M. (2014). Zapatista corn: A case study in biocultural innovation. Social Studies of Science, 44(6), 874-900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312714540060

Commission for Indigenous Development [CDI] (2002), Socio-economic Statistics of the Indigenous Communities in Mexico, http://www.cdi.gob.mx/index.php?id_seccion=91, Accessed on 30 October 2013.

Darlington, S., & Gillespie, P. (2017). Mexican farmer’s daughter: Nafta destroyed us. CNNMoney. https://money.cnn.com/2017/02/09/news/economy/nafta-farming-mexico-us-corn-jobs/index.html

Ebner, N., & Crossa, M. (2019, October 11). Maquiladoras and the exploitation of migrants on the border. NACLA. https://nacla.org/news/2019/10/03/maquiladores-exploitation-migrants-border

Fierros-González, I., & Mora-Rivera, J. (2022). Drivers of Livelihood Strategies: Evidence from Mexico’s indigenous rural households. Sustainability, 14(13), 7994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137994

Figueroa, L. (2016, September 24). Maquila industry keeps workers in poverty, study says. Las Cruces Sun News. https://www.lcsun-news.com/story/news/2016/09/24/maquila-industry-keeps-workers-poverty-study-says/91052154/

Forbes, J. D. (2010). A Native American perspective on NAFTA. Cultural Survival. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/native-american-perspective-nafta

“Free trade agreements are an engine of poverty and inequality”. Interview with José María Oviedo. Bilaterals. (2023). https://www.bilaterals.org/?free-trade-agreements-are-an

Gahman, L. (2017, August 27). Mexico’s Zapatista movement may offer solutions to neoliberal threats to Global Food Security. Truthdig. https://www.truthdig.com/articles/mexicos-zapatista-movement-may-offer-solutions-to-neoliberal-threats-to-global-food-security/

Godelmann, I. R. (2023, May 5). The Zapatista movement: The fight for indigenous rights in Mexico. Australian Institute of International Affairs. https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/news-item/the-zapatista-movement-the-fight-for-indigenous-rights-in-mexico/

Hernández, C., Perales, H., & Jaffee, D. (2022). “Without food there is no resistance”: The impact of the Zapatista conflict on Agrobiodiversity and seed sovereignty in Chiapas, Mexico. Geoforum, 128, 236–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.08.016

ICT. (2018). Chiapas Maya hold-off bio-prospecting . ICT. https://ictnews.org/archive/chiapas-maya-hold-off-bio-prospecting

Imran, Y., Wijekoon, N., Gonawala, L., Chiang, Y. C., & De Silva, K. R. D. (2021). Biopiracy: Abolish Corporate Hijacking of Indigenous Medicinal Entities. TheScientificWorldJournal, 2021, 8898842. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8898842

Indigenous peoples in Mexico. Minority Rights Group. (2024, April 12). https://minorityrights.org/communities/indigenous-peoples-4/#:~:text=Conditions%20were%20exacerbated%20by%20a,sector%2C%20subject%20to%20increasing%20privation

Institute for National Strategic Studies (1998). Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) insurgents in Mexico. [Photograph] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EZLN_insurgents_in_Mexico.png

Kilhart, K. (2016, July 1). Free trade dismantling lives, cultures in Mexico. Grassroots International. https://grassrootsonline.org/learning_hub/free-trade-dismantling-lives-cultures-in-mexico/

Massa, P. (2003) Sign Indicating the entrance of Zapatista rebel territory. “You are in Zapatista territory in rebellion. Here the people command and the government obeys” [Photograph]. https://www.flickr.com/photos/phauly/104794/

Nafta is killing tradition of corn in Mexico. Grassroots International. (2007, November 1). https://grassrootsonline.org/learning_hub/nafta-is-killing-tradition-of-corn-in-mexico/

Nevarro, S. (2014). (issue brief). Inside Mexico’s Maquiladoras: Manufacturing Health Disparities. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/schoolhealtheval/documents/StephanieNavarro_HumBio122MFinal.pdf

Pérez Velasco Pavón, J. C. (2014). Economic behavior of indigenous peoples: The Mexican case. Latin American Economic Review, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40503-014-0012-4

Rocha, M. P. (2023, December 17). Trinational solidarity can protect Mexican food sovereignty from GM corn. Common Dreams. https://www.commondreams.org/opinion/gm-corn-mexico#:~:text=For%20Mexico%2C%20NAFTA%20meant%20abandoning,that%20organized%20crime%20has%20filled

Salas, T. (2021, April 16). Food sovereignty in the Zapatista movement. The University of Sheffield. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/geography/news/food-sovereignty-zapatista-movement

World Bank. (2022). Employment in agriculture (% of total employment) (modeled ILO estimate) – Mexico. World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.AGR.EMPL.ZS?end=2022&locations=MX&start=1991&view=chart

White, M., Gammage, S., & Paez, C. S. (2003). (rep.). NAFTA and the FTAA: Impact on Mexico’s Agricultural Sector. Women’s Edge Coalition. https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/NAFTA_and_the_FTAA_Impact_on_Mexicos_Agricultu.pdf

The library is dedicated to the memory of Secwepemc Chief George Manuel (1921-1989), to the nations of the Fourth World and to the elders and generations to come.

access here