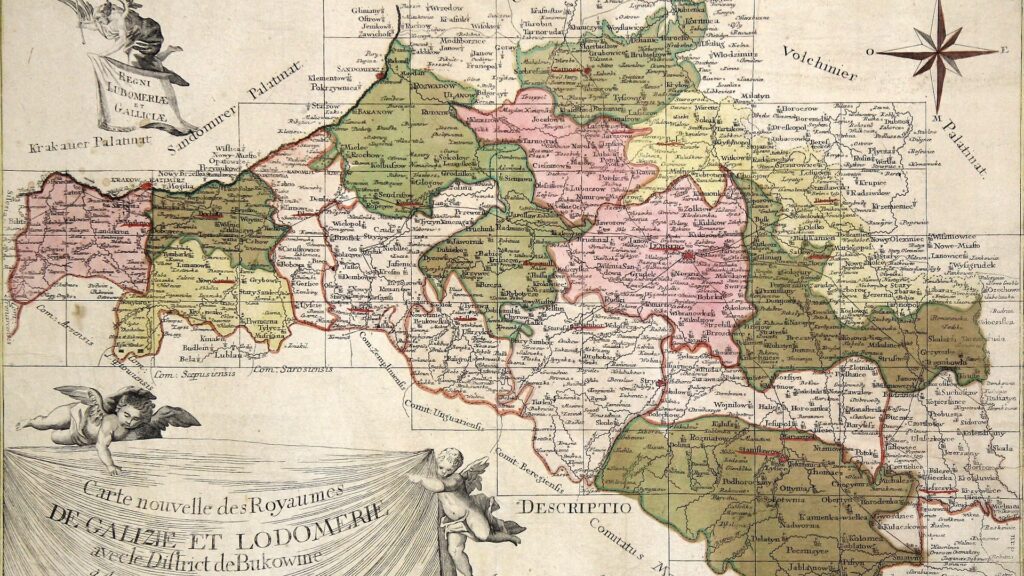

Map of Galicia and Lodomeria, 1780. By Liesganig v. J. M. Probst d. Jüngere. Source: ZVAB / Wikimedia Commons.

Map of Galicia and Lodomeria, 1780. By Liesganig v. J. M. Probst d. Jüngere. Source: ZVAB / Wikimedia Commons.

Ukrainian nationalism is a 19th-century phenomenon that originated in, and was confined to, the Polish territory that the Habsburg Empire annexed in the First Partition of Poland in 1772, called Galicia or Austrian Poland. (Map 7).

Map 71

First Partition of Poland 1772 (Light green, Galicia, to Austrian Empire)

Ukrainian nationalism arose in urban centers, such as Lviv, where the first legal Ukrainian political organization, the Supreme Ruthenian Council (1848-1851) was established. It promoted Ukrainian as a nationality separate and distinct from Polish and Russian.

The Habsburg Empire encouraged a separate Ukrainian national identity to offset Polish nationalism, which threatened the territorial integrity of the state. The strategy worked. Ukrainian nationalists helped Vienna crush the 1846 Polish Revolt in Galicia.

At the time, urban-based Ukrainian nationalism exercised limited Influence over the rural population of Galicia. Being essentially a Catholic movement, it held less sway over the Orthodox population in what is today the Center, South, and East regions of Ukraine. These lands had been part of the Russian Empire since the 18th-century partitions of Poland. The people considered themselves culturally, religiously, and politically Russian.

This self-identification had been demonstrated during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812, known as the Second Polish War. In the “first Polish war” in 1807, Napoleon had defeated the German kingdom of Prussia. Under the terms of the Treaty of Tilsit, Prussia relinquished territory it acquired in the 18th-century partitions of Poland. From that territory, Napoleon created the Duchy of Warsaw from which he launched his invasion of Russia. Poles comprised the second largest contingent in his invading Grande Armée of 615,000 troops2. On entering Vilnius, Napoleon proclaimed, “Poland is resuscitated; it is for its entire recovery that it is a matter of fighting now.”3

Remembering Polish religious persecution in the 17th Century, the Orthodox population in today’s Center, South and East regions of Ukraine opposed being reincorporated into Catholic Poland. They supported Russia’s Orthodox Czar. Some estimates suggest this population composed 50 percent of the rank and file of the Russian army, 80 percent of junior officers,4 and 20 percent of senior officers. In addition, six regiments of Orthodox Cossacks were part of the Russian Army that occupied Paris in 1814.5

In World War 1, the Orthodox population in the Russian territory that is today the Center, South, and East regions of Ukraine continued to adhere to their loyalty to Russia. Three and a half million fought for the Russian Orthodox Czar, against the 250,000 Ukrainians who fought for the Catholic Habsburg Emperor.6

During World War I, the Habsburg Empire and Imperial Germany attempted to impose an anti-Russian Ukrainian identity on the Orthodox population in Russian territory that today constitutes the Center, South, and East regions of Ukraine. It was psychological warfare termed the “weaponization of ethnicity.” In sponsoring Ukrainian nationalism, Vienna and Berlin were employing a tool by which to destabilize and defeat the Russian Empire. One to be exploited or discarded depending on circumstances.

In 1914, Vienna created “The Ukrainian Legion” as a military detachment of the Austrian Army to expedite the establishment of a Ukrainian state on territories conquered from Russia. It also founded the “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine” as a parallel political organization. Its purpose was to assemble “Russian Ukrainian emigres for political and cultural work. In the autumn of 1914, it published a Manifesto on the Ukrainian Question in multiple European languages whose aim was to promote and popularise its intention to establish a Ukrainian state independent from Russia.”7

For Vienna, the promotion of an independent Ukrainian state was a means by which to defend the territorial integrity of the Habsburg Empire. The fear was that Russia would annex its Slavic province of Galicia — directly through war or indirectly through Moscow’s patronage of the Russophile ideology Pan-Slavism. “In 1913 alone, the Russian Foreign Ministry funnelled 200,000 rubles to the Russophile faction in Galicia.” Such an independent Ukrainian state was to consist of Russian lands, where the people did not consider themselves Ukrainian, not Habsburg territory, where the people did. It was to function as a buffer state between the two empires.

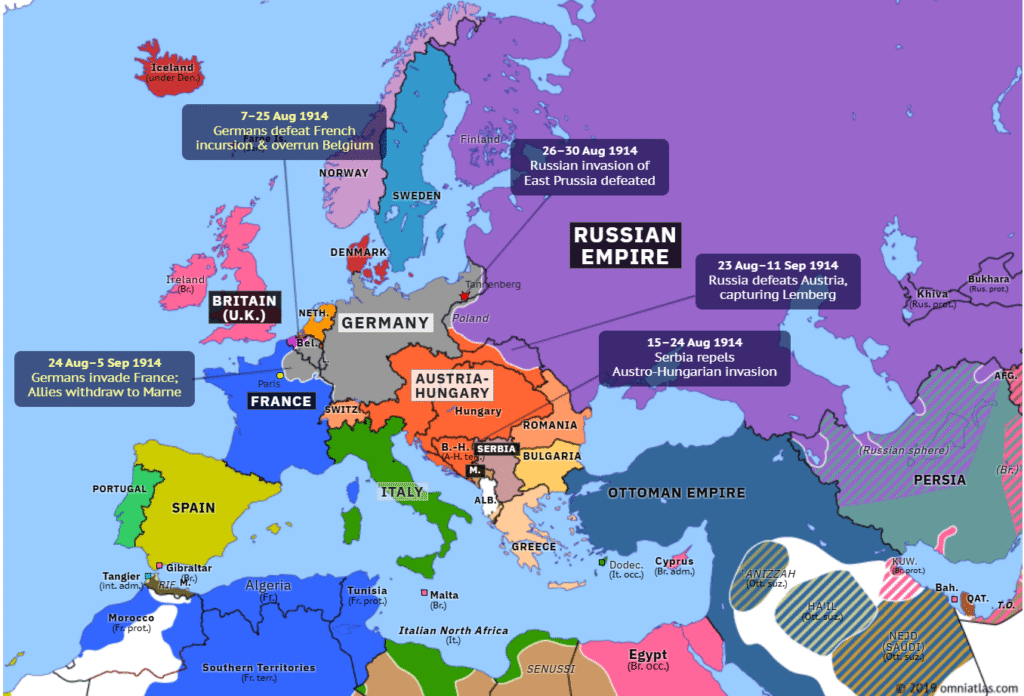

Despite more than half a century of official encouragement of an anti-Russian Ukrainian national identity by the Habsburg Empire, there existed significant pro-Russian sympathy among the population in Galicia. 8 In a series of battles at the outset of the war, Russia defeated the Habsburg Empire and expelled it from Galicia. (Map 8)

Map 89

Europe 1914: The Great Retreat

“As they retreated westwards through Galicia in the autumn of 1914, Habsburg troops perpetrated atrocities against Ukrainians suspected of harbouring pro-Russian sympathies, anticipating the general descent into violence in the province.”10

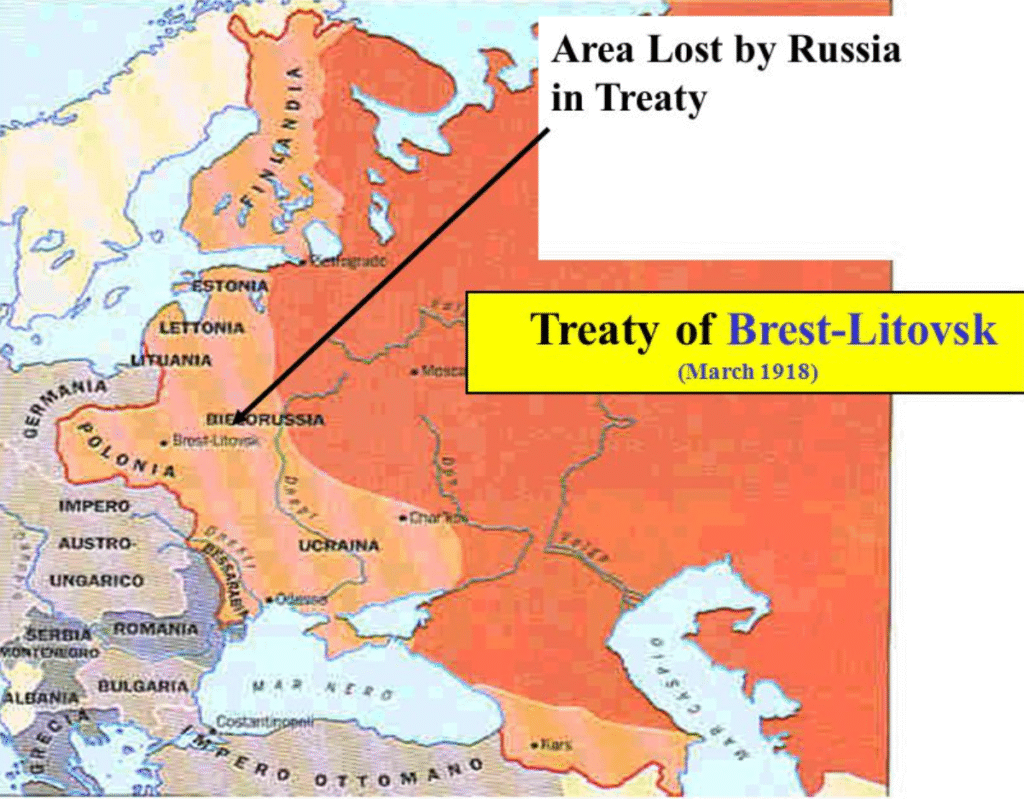

In 1917, as attacks on the pro-Russian population increased instability in Galicia, posing a threat to the integrity of the empire and continuation of the monarchy, Vienna withdrew its support of Ukrainian nationalists. Germany, however, continued to champion Ukrainian nationalism. Berlin’s strategy culminated in a short-lived victory when Lenin’s Bolsheviks, who seized power on November 7, 1917, signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918. By its terms, Lenin surrendered Russian lands acquired in the partitions of Poland to Germany’s Ukrainian allies. (Map 9)

Map 911

By the end of 1918, the Habsburg Empire and Imperial Germany had collapsed. Lenin, believing his Soviet Russia could provoke a Communist revolution in a Europe devastated by years of conflict, launched a war to recover territory lost in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. While defeated in Poland, his Red Army was victorious in Ukraine.

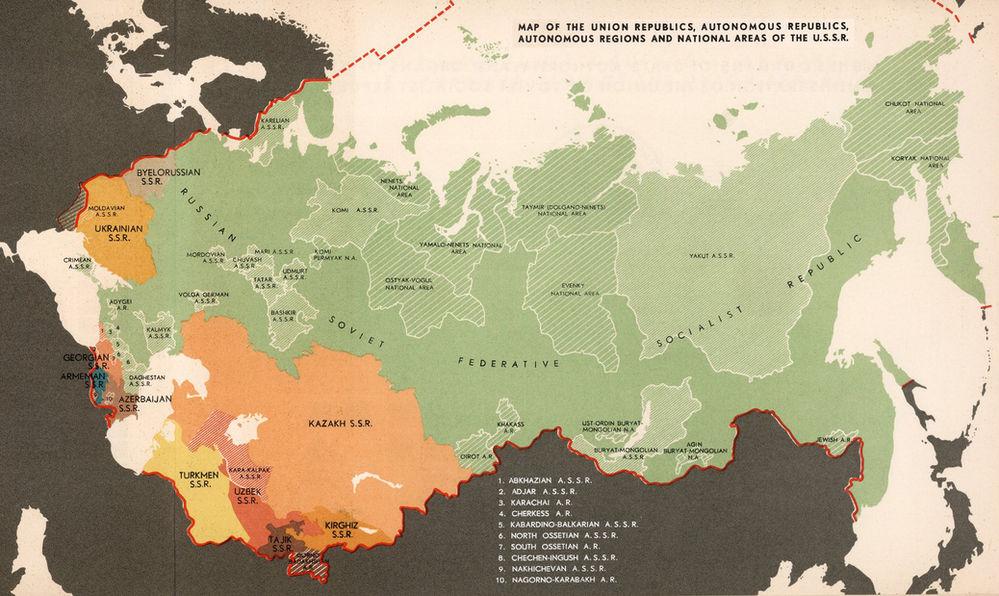

There, Lenin established a Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. It was the precursor to the present-day Ukrainian state, but without Crimea or the western region. (Map 10)

Map 1012

Soviet Ukraine in December 1922

To consolidate Soviet power, and ensure loyalty from a Soviet Ukraine, Lenin implemented a policy of Ukrainization of the party, the government, and the national identity. By such means, a Soviet defined and delineated Ukraine, national in form and socialist in content, would advance world revolution.

Ukrainization was part of Lenin’s policy of korenization or indigenization. The aim was to fragment the Russian Empire into as many non-Russian nations and nationalities as possible, and to eliminate a Russian ethnic presence from the new political entities. In 1926, the Soviet Census listed 190 officially recognized ethnic groups in the Soviet Union. Most of the new national polities were in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). On a map, the RSFSR looked like a piece of Swiss cheese. (Map 11)

Map 1113

Ethnic units of RSFSR in various shades of green with and without diagonal lines

Korenization was a model of “divide and rule.” Each officially recognized national minority, however small, was awarded its own territory. “…the Bolsheviks appeared to be the first state to institutionalise ethnoterritorial federalism, classify all citizens according to their biological nationalities and formally prescribed preferential treatment of certain ethnically defined populations”14

However, ethnic minorities that found themselves within the borders of these new polities were to be assimilated into the officially recognized ‘national’ population. For example, Tajiks in Uzbekistan were “Uzbeks.” Pamiris in Tajikistan were “Tajiks.”15

In the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Ukrainianization was used to compel Russians, Russian-speaking Ukrainians, and ethnic minorities to adopt the Ukrainian language, culture, and national identity. It was a continuation of the policy by Vienna and Berlin to weaponize ethnicity.

A Ukrainian state was to be made ethnically homogenous through forced assimilation, mass deportations, or mass executions. This was attempted by the Soviets before World War II, the Nazis during World War II, and the Soviets, again, after World War II.

Imposing a uniform Ukrainian identity on the entire population was further complicated when the borders of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic were expanded. In 1945, Stalin annexed Polish and Czechoslovakian territories to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1954, Khrushchev transferred jurisdiction of the Crimean peninsula from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

In post-Soviet Ukraine, the weaponization of ethnicity has focused on forced assimilation.

1 Dominik Collet, “Abusing Climate: The 1770s Anomaly and the First Partition of Poland–Lithuania,” Acta Historica Tallinnensia, 29(2):190, January 2023, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Polish-Lithuanian_Commonwealth_1773-1789.PNG

2 “Polish Troops of the Napoleonic Wars,” Napoleon, His Army and Enemies. http://napoleonistyka.atspace.com/polish_army.html

3 François Lelouard, “1812: The Second Polish Campaign,” The Napoleon Series, 1995 – 2017. https://www.napoleon-series.org/military-info/battles/1812/Russia/1812The2ndPolishCampaign.pdf

4 “Ukraine in Russian-French war years 1812-1814,” geomap.com, https://geomap.com.ua/en-uh9/363.html

5 Ukraine in Russian-French war years 1812-1814,” geomap.com, https://geomap.com.ua/en-uh9/363.html

6 Orest Subtelny, Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press, 2000, p. 340. https://archive.org/details/ukrainehistory00subt_0/page/340/mode/2up

7 Borislav Chernev, “The Habsburg Mobilisation of Ethnicity and the Ukrainian Question during the Great War,” Austria-Hungary’s imperial challenges: Nationalisms and rivalry in the Habsburg Empire around 1900, Max Weber Foundation – German Humanities Institutes Abroad, 2020, https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/pnet_derivate_00002013/ethnicity.pdf

8 Borislav Chernev, “The Habsburg Mobilisation of Ethnicity and the Ukrainian Question during the Great War,” Austria-Hungary’s imperial challenges: Nationalisms and rivalry in the Habsburg Empire around 1900, Max Weber Foundation – German Humanities Institutes Abroad, 2020, https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/pnet_derivate_00002013/ethnicity.pdf

9 “Europe 1914; The Great Retreat,” Omniatlas, https://omniatlas.com/maps/europe/19140905/

10 Borislav Chernev, “The Habsburg Mobilisation of Ethnicity and the Ukrainian Question during the Great War,” Austria-Hungary’s imperial challenges: Nationalisms and rivalry in the Habsburg Empire around 1900, Max Weber Foundation – German Humanities Institutes Abroad, 2020, https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/pnet_derivate_00002013/ethnicity.pdf

11 Adrian Bonenberger, “Brest-Litovsk: Eastern Europe’s Forgotten Father,” The United States Foundation for the Commemoration of the World Wars, 2013-2024 https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/articles-posts/4094-brest-litovsk-eastern-europe-s-forgotten-father-2.html

12 “The Soviet Ukraine in December 1922,” The World on the Map, https://www.edmaps.com/html/map_ukraine_december_1922.html

13 Nick Routley, “Four historical maps that explain the USSR, ”Visual Capitalist, February 26, 2022, 4 Historical Maps that Explain the USSR

14 Galym Zhussipbek , History of the Central Asian Region – 1700 to 1991,” Legacies of Division: Discrimination on the Basis of Religion and Ethnicity in Central Asia,” (9) HISTORY OF CENTRAL ASIA – 1700 TO 1991 | galym zhussipbek – Academia.edu

15 “Pamiris in Tajikistan,” Minority Rights Group, March 2023, https://minorityrights.org/communities/pamiris/

16 “The battle for Russian language in Ukraine,” Gateway House, November 3, 2022, https://www.gatewayhouse.in/the-battle-for-russian-language-in-ukraine

17 Sergiy Panasyuk, “The Use of Russian Language in Ukraine in Wartime,” Oxford Human Rights Hub, June 26, 2023, https://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/the-use-of-russian-language-in-ukraine-in-wartime/

18 “Rakshit Sharma, “Ukraine fines Kharkiv mayor for using Russian language on social media posts,” Firstpost, February 23, 2023, https://www.firstpost.com/world/ukraine-fines-kharkiv-mayor-for-using-russian-language-on-social-media-posts-12196782.html

19 Carol Schaeffe ,“‘A Book is a Quiet Weapon’,” The New York Review, April 21, 2023, https://www.nybooks.com/online/2023/04/21/derussification-ukraine-libraries/

20 Rakshit Sharma, “Ukraine fines Kharkiv mayor for using Russian language on social media posts,” Firstpost, February 23, 2023, https://www.firstpost.com/world/ukraine-fines-kharkiv-mayor-for-using-russian-language-on-social-media-posts-12196782.html

21 Rakshit Sharma, “Ukraine fines Kharkiv mayor for using Russian language on social media posts,” Firstpost, February 23, 2023, https://www.firstpost.com/world/ukraine-fines-kharkiv-mayor-for-using-russian-language-on-social-media-posts-12196782.html

22 Rakshit Sharma, “Ukraine fines Kharkiv mayor for using Russian language on social media posts,” Firstpost, February 23, 2023, https://www.firstpost.com/world/ukraine-fines-kharkiv-mayor-for-using-russian-language-on-social-media-posts-12196782.html

23 “Zelensky Signs Law Banning Russian Place Names in Ukraine in Struggle Over National Identity,” The New York Times, April 22, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/22/world/europe/zelensky-russian-ban-ukraine.html

24 Patrick Reevell, “Ukraine moves towards separate church, as conflict with Russia leads to major schism,” ABC News, December 17, 2018, https://abcnews.go.com/International/ukraine-moves-separate-church-conflict-russia-leads-major/story?id=59863139

25 “Zelenskiy Signs Law Banning Russian Orthodox Church In Ukraine,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, August 24, 2024, https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-russia-orthodox-religion-ban/33091200.html

The library is dedicated to the memory of Secwepemc Chief George Manuel (1921-1989), to the nations of the Fourth World and to the elders and generations to come.

access here