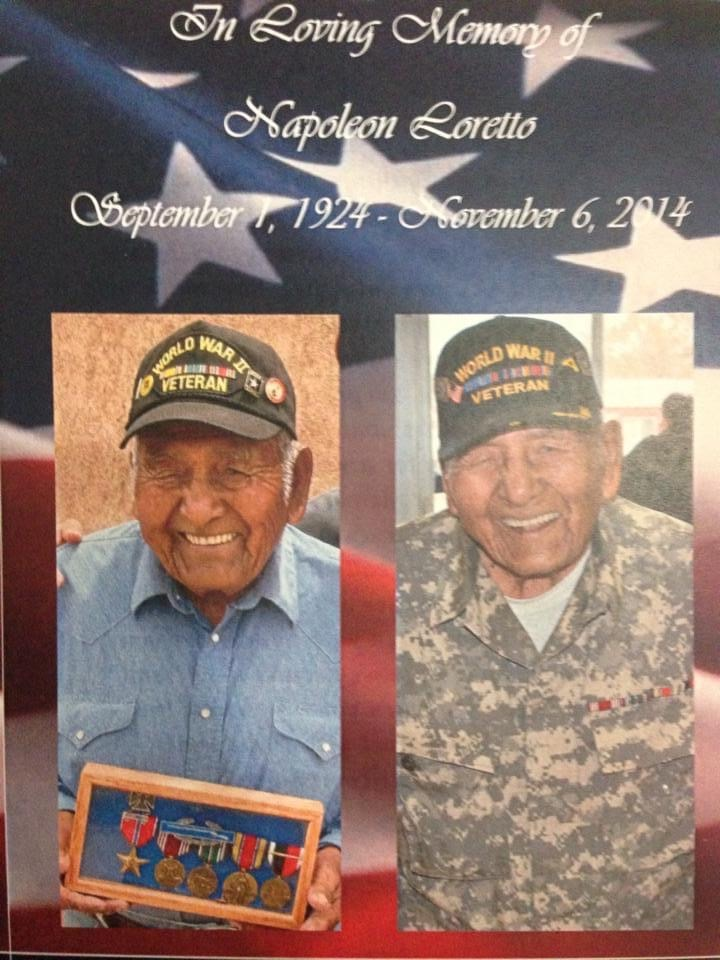

Napoleon Loretto, PFC

U.S. Army – World War II

1943-1946

Interviewed and researched by A. Alex Sando,

April 11, 2006 – January 8, 2008

Interviews were person to person in Towa language

On June 23, 1943, I was 20 years old when I left Jemez Pueblo to enter basic training at Main Wells, Texas located near Abilene. Because there was no transportation available, it was difficult to leave my village. My father Manuel helped me by walking to the Jemez Mission Post Office to ask the mail carrier if he could give me a ride. The mailman gave me a ride to Tony Montoya’s store in San Ysidro; from there I hitched a ride from a logging truck. The truck driver stopped for me and asked where I was going. My response was, “I am going to the military.” The driver quickly said, “Jump in.” There were several young men at Bernalillo waiting to catch a bus to Albuquerque. We all boarded the bus for Albuquerque. From there we traveled by train to El Paso and on to Main Wells. We were told not to take any extra clothes because the Army will issue them. I traveled only with what I was wearing.

After basic training, on Christmas in 1943, I received my orders for Casa Blanca, North Africa. Along with several soldiers, we traveled from Texas to West Virginia, and on a ship to North Africa. We did not do much in North Africa. We waited for two months, and in February 1944, we left for an assignment in Naples, Italy. We were there for six months of training. We were always moving to different places in Europe. On August 1, 1944, we were told we would be leaving Naples for another location in Europe. Finally, a week later on August 7, 1944, we left Naples by ship. On August 15, 1944, which is Zia feast day, we arrived in the north of France. We were there for 8 days only to survive on sea rations. That’s all we ate!

In addition to myself, there were several Jemez men who also served in Europe. They were Felix Fragua, Juan Toledo, Frank I. Sando, John D. Mora, Hilario Armijo, Mathew Waquie, Guadalupe Chosa and Joe Colaque (Chicken Little in Towa language).

Unfortunately, I did not meet with any of the men except for Joe. We met at a place on the Germany and French border. He did not recognize me right away, but it did not take very long for us to start talking Towa, our native Jemez language. It was most enjoyable meeting with Joe Colaque to share lunch and the opportunity to converse in Towa for four hours. It was the only time period we had before he left for the front lines.

A Jemez man, John D. Mora was captured by the Germans 75 miles from Rome. He was one of many prisoners of war (POWs) that were marched for many miles each day, a brutal tactic to rashly kill the American soldiers. The Americans and Germans had difficulties communicating, but this was an advantage to prepare an escape plan. The plan allowed one fellow soldier to take command for the Americans. The soldier instructed his men, “If anyone is going to be killed, this is it. There are a lot of us here and what we will do is every one of us will yell at the top of our lungs to distract the German guards and we will immediately attack them. This strategy worked well as all the German guards were killed and the Americans escaped. This is how John was saved.

One day on the battlefield, Joe Colaque met John D. Mora. Joe saw a man sitting in a foxhole and approached him. Not recognizing the man, Joe said hello to him and asked: “Where are you from?” John responded by saying Jemez. In much surprise, both introduced themselves in Towa, “I am Deh’loa’cu” [Chicken Little], and “I am Heh’lah”, [Over Beyond].

Later after the war, Joe and I met in Jemez. He talked about the time when he met a Jemez man in a foxhole in Germany. Joe was confused and insisted he met me in the foxhole at Germany. I said no to him, it was not me it was John that you met. He kept insisting he met me in the foxhole, and I said no to him again, it was John.

In 1945, I spent Christmas in France. That Christmas night we were attacked by the Germans. They shelled one of our gas trucks and it burst into flames. The flames were so bright it was almost like daylight. It was like having Christmas lights on that cold night in Germany.

We were not allowed to enter Paris because during wartime, the military was restricted from entering any city. However, we continued to move on further into Germany until we arrived at the Rhine River. The raging river was far below us as we stood watching from a cliff above. A phantom bridge was built across the wide river for soldiers, weapon carriers, and tractors to cross. There were two elder soldiers in our group. They were both at least 60 to 70 years old and had fought in World War I. It was their second war; the elders were fighting. Before we arrived at the river, the elders said, during WWI we were in this area and we inscribed our initials on a rock by the bridge. Sure enough, we approached the bridge and found their initials still inscribed on a huge boulder above the river. Soon after the war ended, the twosome was the first to return to the states. They were much older and had served in two wars. They received their orders to return home before us much younger soldiers.

Munich is a large city near the Rhine River. There are other smaller towns located nearby with German names. I do not remember all the names. One night when we were near Munich, we were told to kick in and get some rest. Lazily, we dug shallow foxholes in the hard ground, and slept in them that night. When we woke up early the next morning we were stunned by the hundreds and hundreds of American planes flying across the sky above us. The planes looked like huge bundles of clouds, there were so many. It was difficult to even see the sun. Thousands of bombs were dropped during the ordeal; a second command was given to the pilots to return and bomb the same area again. The bombing that day helped end WWII, and it was the last time the Germans were hit hard with no resistance.

When I was overseas, I always carried a journal with me to write about my military experiences. I wrote lots of things that happened, but it was stolen from me while I was in North Africa or Italy. Anyway, in June of 1945, the Germans surrendered, and World War II ended. We did not know the war ended until about two days later. All the buildings in Munich (what was left) were vacated. Doors were freely left open and there was nobody in the city anymore. The bars were not attended so we helped ourselves to the drinks, and everyone partied and became drunk.

The next day, we combed the vacated city, homes were confiscated with weapons, even toy guns. We piled all the weapons so high; about as high as the utility pole outside. Napoleon was pointing with his finger from inside his home in Jemez. It took us about two weeks to confiscate all the weapons only to gas and burn them. Ashes and metal pieces were left on the ground.

All the Germans in the area were captured and incarcerated in their own stockades. Even 12 years old children were put in jail too, because they were as good marksmen, like the German soldiers. They could kill. Also, at that time five German leaders were put in a concentration camp. We guarded them with machine guns and other weapons. Soon after, the leaders were transported out of the area.

Before I came home to Jemez Pueblo, I had some beautiful weapons with me. I dismantled two of them and mailed them home. One was a Chinese carbine and a Czechoslovakian weapon. I kept the weapons at my father’s house for many years until one day I learned that the carbine was missing. Guess where I found it? At the Jemez Springs bar hanging on the wall. One time, I approached the owner and I told him that the gun belongs to me. The bar owner asked me, can you prove it? Sure, I answered. I did not have the serial number to prove the gun was mine, so I could not get it back. Also, before coming home from overseas, I sent another gun home, an Italian carbine. It was short, something like a 30-30 rifle. Another was a Czechoslovakian pistol, which I do not have anymore. Also, I brought home with me a German bayonet. It had a beautiful silver eagle design with a nice curved-shaped handle. I lost that too.

In Austria, below the German border is where Hitler lived. It was a secured place located just outside his country, Germany. After the war was over, they stationed us there at his place. Two soldiers guarded for two-hour shifts. The small building was built with 75 steps on the exterior. I stood guard at the top near the stairwell. The building structure had guardrails in a circular fashion to protect us guards from falling off. Gosh, it was also very cold there.

In December 1945, we were told that we will be coming to stateside, and we will be home for Christmas. We were so happy that we were finally coming home. On December 17, 1945, hundreds of American soldiers boarded on three separate large ships and set sail for New York City. Shortly after being out on the sea, we were told that a strong and terrible storm was coming in. We were all placed and locked in the lower level of the ship. We were not allowed on the deck. The storm was so strong, it would have easily turned over our ship and every one of us would have drowned.

Finally, two weeks later we arrived in New Your City passing by the Statue of Liberty. We were finally allowed to step off the ship and onto the deck. We were all happy to survive the storm but very sick from the two weeks we spent traveling below the deck of the ship. We boarded on a ferry and were transported to the New York docks. When we arrived in the big city, we were not allowed to go anyplace. After getting off the ferry, we were asked to walk along a chain link fence and not to shake hands with anybody. I do not know why we were not allowed to shake hands. We were not harmful and did not want to hurt anyone. We were sent to Boston, and other soldiers to different cities along the eastern seaboard. Our Sergeant said, “You guys are on your own, take your showers and eat breakfast.” Eat breakfast? We do not have any money. Before leaving overseas, we were told to bank our money with the commanding officers. It consisted of francs, liras and other foreign monies that was recorded and to be exchanged when we got to New York. Well, we did not get anything, we were all broke!

On New Year’s Day 1946, we had no money. A ranking officer approached me and said, “Hey Chief, come let us go to the club.” “Why, I cannot go because I got no uniform that has E-5 stripes.” Another soldier said, “I have one.” He loaned me his uniform, I put it on and went to the club with the officer. When we arrived at the club, we learned that ranking did not matter. No lie, everyone was there. The officers bought all the drinks for us. They said to just set them up and we drank. The next day I woke up wondering how I got to the barracks.

From Boston, we took a train to El Paso, Texas. It took four days to get there. On January 9, 1946 I got my discharge; they gave me some money and I came home. One time I was in Bernalillo at an elders’ home to have my income tax done. A man asked me, “Have you been in the service?” I said, “Yes sir.” The man replied, “I was in too.” He asked me, “Where were you at?” “Germany.” “What year?” “1945.” The man asked, “Did you see the bombers go by? I was one of the bombardiers.” The man was John from Corrales, New Mexico.

One year, we had a reunion in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I wore my WWII cap. A man asked me, “Where were you at, Munich?” I said, “Yes.” The man said I was one of the bombardiers too. Another year, we had another reunion in Indianapolis, Indiana. I received an invitation to come. I arrived at the hotel in a taxi and I noticed that they had a sign displayed with our company name, Company D., 45th Division. A friend found out that I was there. Right away, he came down from his room to meet with me. His name is Henry L. Humphrey, a white guy from Alabama. He and two other guys, Art and John and I were always together. Henry was in a wheelchair when we met. When he saw me at the hotel lobby, he yelled at me, “Hey, here comes the Dead Man”. He thought I was killed when our jeep drove over a mine and threw us all over the place. I did not know what happened until I woke up in a Munich hospital on November 12, 1945. I did not know what happened to the driver and my other partners. It was a terrible blast, but I managed to survive. The jeep, I was informed was destroyed and shattered to pieces.

Napoleon Loretto was born on September 1, 1923. He received a Purple Heart about two years before he walked on, on November 6, 2014.

The library is dedicated to the memory of Secwepemc Chief George Manuel (1921-1989), to the nations of the Fourth World and to the elders and generations to come.

access here